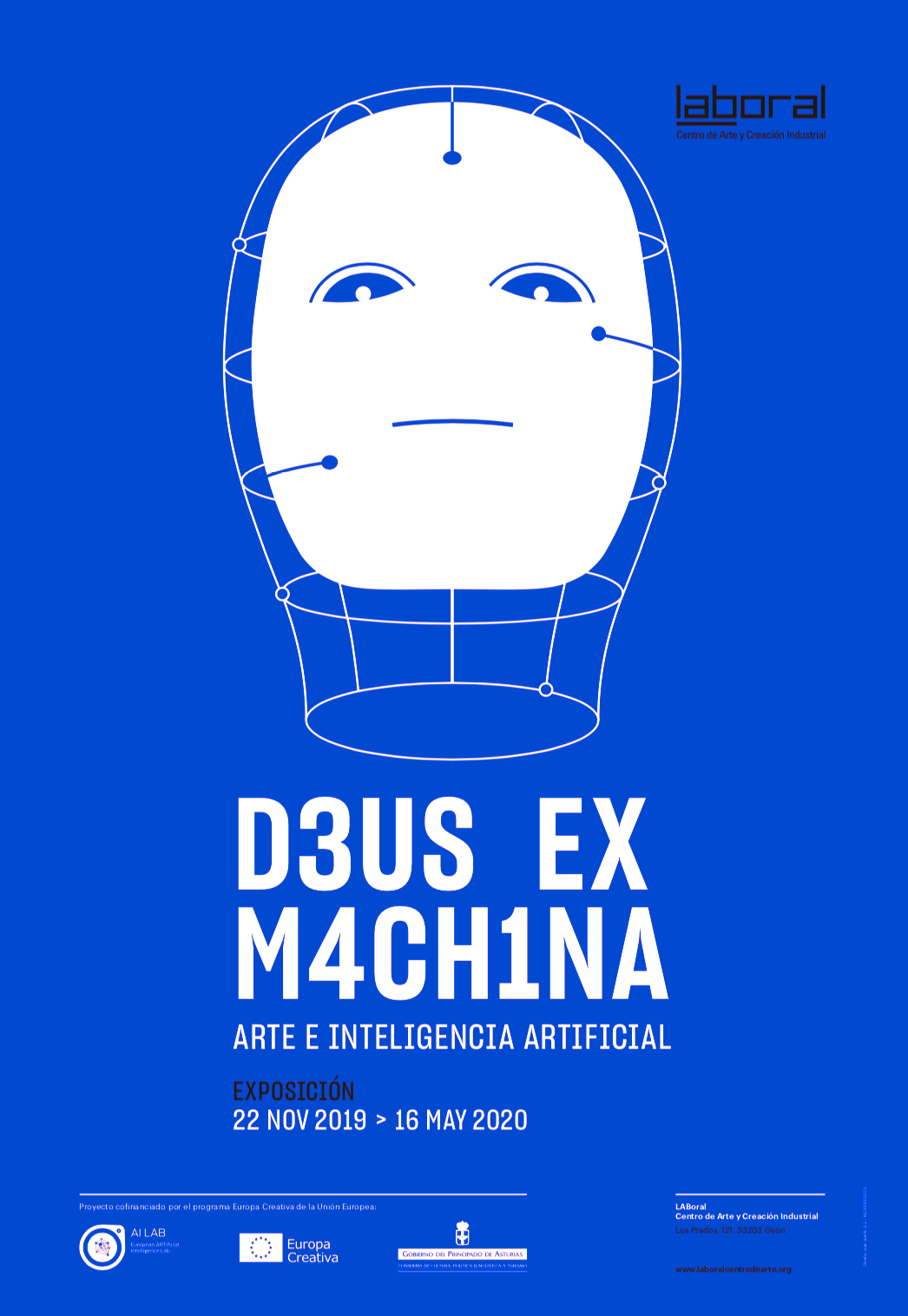

D3US EX M4CH1NA. Art and Artificial Intelligence

LABoral Centro de Arte de Creación Industrial, Gijón (Spain)

November 22, 2019 – May 16, 2020

Karin Ohlenschläger and Pau Waelder

Exhibition curators

Downloads

Exhibition booklet (PDF, Spanish/English)

Essay by Pau Waelder (PDF, Spanish)

Essay by Pau Waelder (PDF, English)

Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is behind most of our interactions with computers and digital devices, apps and social media. Every time we use a computer, smartphone or tablet to consult a map, to post contents on social media, to look for information on the Internet or to find new music or series, we are supplying data to the companies providing these services. When we give orders to Siri or Alexa, we are teaching the system to understand what we say and to memorize our actions. The more we learn thanks to computers, the more they learn about us. All the data we generate without being aware of it help the artificial intelligence systems of large corporations to know what we are actually doing as well as our desires at the present moment, and in consequence to predict what we will do or wish for in the future.

The potential of artificial intelligence is so great, and our knowledge of what it really does is so limited, that the discourses surrounding it are indistinctly driven by both myths and facts. In recent years, the big tech companies have been competing directly with one another to lead the development of AI, which has led to spectacular applications of this technology to specific solutions, but also to ambitious statements about what we will be able to do in the near future. Undoubtedly, the idea of an intelligent machine raises great hopes but also arouses apocalyptic fears, given that, for humankind, machines, inasmuch as mere instruments, have brought about unimaginable progress but also terrible devastation.

As a result, the development of AI is shrouded in stories, some of which describe real innovations, that manage to cure illnesses, predict time, organize work, improve translations, provide entertainment or look after the environment. Others reflect the bold expectations of scientists, corporate ambitions, or our own hopes and fears towards a machine which we don’t completely understand. The way in which artificial intelligence programs, able to process millions of data in milliseconds, respond to our requests or even anticipate our wishes almost seems like magic, and very often this has led us to expect much more from AI than it can actually deliver.

A simple solution to resolve a complex situation is as old as the ages: in ancient Greek theatre a machine, often a crane, was used to bring an actor onto the stage who would play the role of a god and decide the denouement with the authority of an omnipotent being. In Latin this convention was called deus ex machina, and this device introduced a short-cut that broke the coherence of the plot but provided a satisfactory and spectacular end to a complex situation, however implausible it might be. Artificial intelligence appears to us now like a deus ex machina, an artificial solution that promises to accelerate the denouement of our problems. A world in which everything is resolved by processing data and in which many of our everyday concerns (whether discovering made-to-measure products, searching for employment or finding a mate) can be resolved by a program in fractions of a second. However, nothing is that simple: the development of artificial intelligence brings with it challenges and risks that cannot be overlooked.

For AI to write a text like a human, to speak with a person or recognise a face, it needs thousands of texts, audio recordings and photographs, which must also be authentic, taken from real people and situations. To this end, companies like Google, Apple, Facebook or Amazon use the data generated by their users, the contents of social media and public forums, countless books, photos and videos stored in their servers, as well as the recordings and other data obtained from the devices they commercialize. This vast volume of information did not exist a few years ago, and is one of the factors behind the recent explosion of AI. A more sophisticated artificial intelligence therefore requires us to cede our data and to renounce our privacy. But this is not the only thing that the current development of AI will force us to renounce. Artificial intelligence programs process the information they receive using algorithms we ignore. Very often, the compilation and distribution of these data brings into the open all kinds of prejudices and inequalities. And though they ought to be corrected, they run the risk of being perpetuated in the system’s learning pattern.

On the other hand, there are factors derived from the very materiality of this technology that produces considerable energy costs: training an AI system with a large volume of data can generate up to 284,000 kilos of carbon dioxide, equivalent to the emissions of five cars throughout their whole use life. The carbon footprint, one of the most worrying aspects of information and communication technologies, also affects the development of some AI systems. This not only has consequences for the environment but also for the very access to technology that makes more advanced artificial intelligence possible.

AI is not magic, nor is a neutral and inevitable force. It is a set of algorithms and computation techniques that have to be observed and questioned in order to prevent them from generating inequality or perpetuating prejudices. Therefore, it is necessary to create a framework for reflection on this technology that allows us to apply a critical gaze at all times. And not to negate what it provides us, but to understand its functioning and our implication in it. Art which appropriates scientific and technological advances creates a cultural framework that enables us to understand them, experiment with them and develop a more realist and also more engaged critical stance.

The exhibition D3US EX M4CH1NA. Art and Artificial Intelligence invites us to reflect on the expectations and fears aroused by the idea of an intelligent machine.

The selection of artistic projects is divided into five thematic areas. The first consists of projects that call into question the notions of creativity, originality and authorship (Harold Cohen, Anna Ridler). They also invert the relationship between the spectator and the work, turning the visitor into the object of study for robots and AI algorithms (Patrick Tresset).

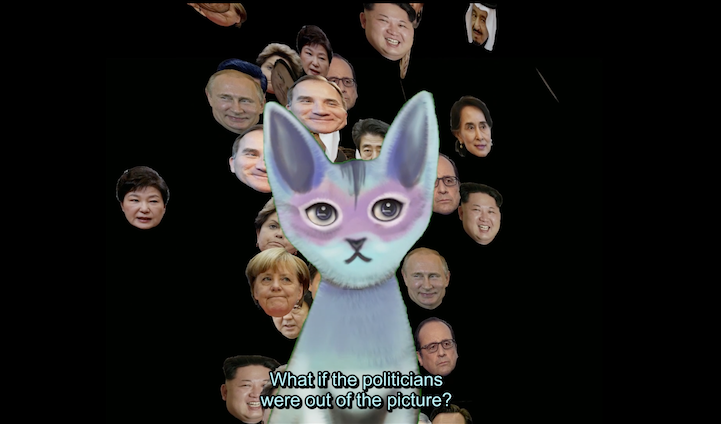

The second group contains projects that explore the potential of AI as a system for analysis, control and surveillance, related with the future of employment (Guido Segni), privacy (Lauren McCarthy) or the governance of the world by an AI algorithm (Pinar Yoldas).

The third group examines the apparent impartiality of AI and throws light on value and behavioural patterns that can replicate prejudices or increase inequalities of all kinds (Memo Akten, Caroline Sinders).

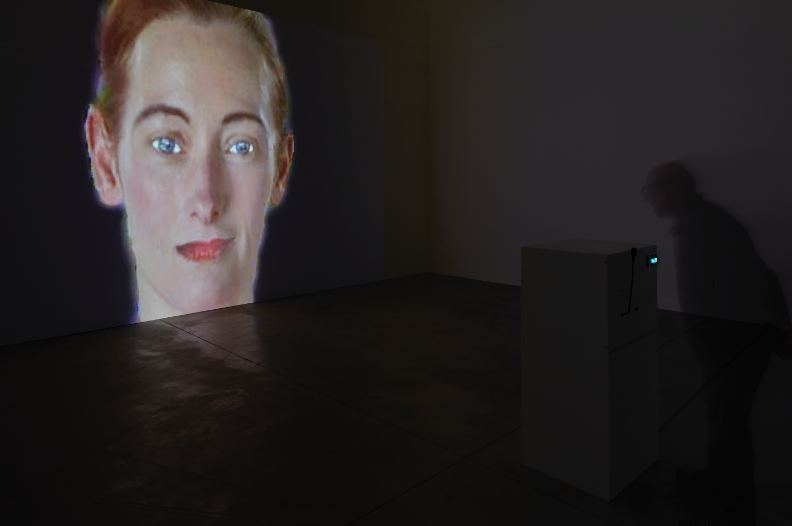

The fourth group invites visitors to experience a dialogue with an AI system by means of a conversation with this artificial otherness (Lynn Hershman Leeson) or by means of body language and gestures (Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau), confronting each spectator with his or her own virtual double.

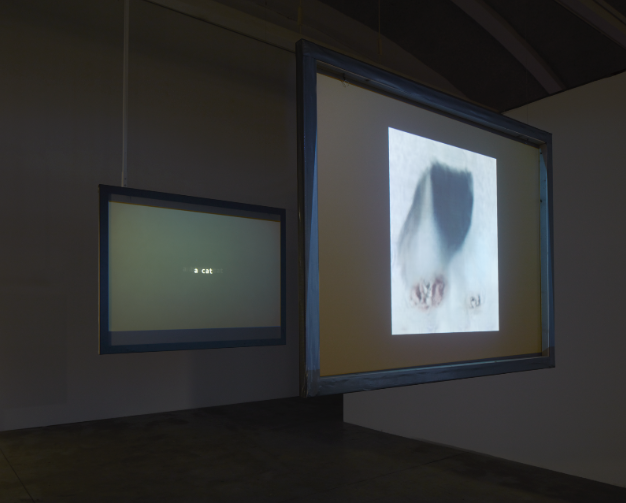

The final group of works highlights how, for some time now, machines have been communicating with each other independently. In some cases, as they take place without the intervention of human presence (Felix Luque, Jake Elwes), these interactions transmit a sense of wonder or unease. Meanwhile, other works induce us to rethink our anthropocentric idea of the communication and evolution of natural and artificial systems (Jenna Sutela).

The thirteen installations –which include generative, audiovisual and interactive works – are created by artists who have accrued considerable prestige both here in Spain and internationally. Taken overall, they draw a broad panorama of artificial intelligence from different perspectives and approaches. At the same time, they invite us to reflect and explore new technological, social and cultural situations posed by AI in relation to the management and perception of our surrounding environs and everyday forms of behaviour.